Historic Chemical Substitutions, Part 2: CFCs

It seems like every day there are more headlines about PFAS, a.k.a “Forever Chemicals”, each one identifying more health risks, more places they've been detected, more bans and more regulations.

From the beginning, Actalent has been following PFAS bans and substitution programs closely in our Q&A series, Forever ... For Now. As a society, it’s clear we know and accept that the health risks associated with PFAS greatly outweigh the benefits.

Now comes the process of replacing them.

The prevalence of “forever chemicals” and our reliance on them — they’ve proven extremely useful and effective in everything from long-lasting cosmetics to heat-resistant firefighting foam — will make the transformation anything but simple.

In fact, the process will require major adjustments, both in how we make and use a multitude of affected products.

The good news is we’ve done this before.

In this series, Historic Chemical Substitutions, we’re examining some of the most successful chemical substitution campaigns in history.

Hopefully these examples will serve as reminders that we’ve adjusted, innovated and overcome challenges like PFAS before. And in making these changes, we’ve often achieved better outcomes for the greater good — outcomes that may not have been endeavored otherwise.

In Part 1, we examined asbestos. In Part 2, we turn to the sky for a look at CFCs (chlorofluorocarbon gas).

What are Chlorofluorocarbon Gases (CFCs)?

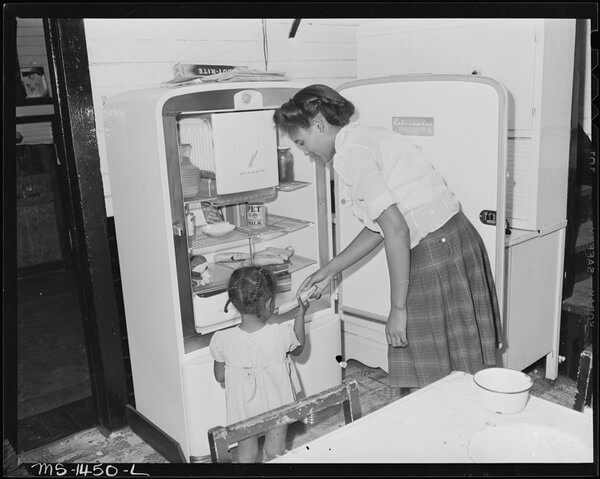

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, toxic gases like chloromethane and ammonia were used as refrigerants.

While effective, chloromethane and ammonia are also highly flammable and reactive. This posed a direct danger to consumers, resulting in injuries and even fatalities.

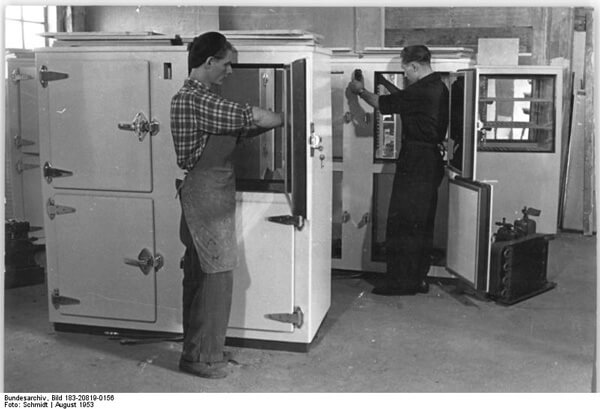

In the 1920s, manufacturers collaborated to invent a stable, non-toxic, non-flammable class of refrigerant known as chlorofluorocarbon gas (CFC). Well-known CFCs include Freon, R-11, and R-12.

CFCs, however, proved to be more dangerous than their predecessors, albeit in a different, much bigger way.

CFCs Impact on the Ozone Layer

Although stable and non-reactive under normal circumstances, CFC gases become reactive with ozone molecules upon reaching the earth’s atmosphere. Those reactions, happening unknown for decades, began breaking down ozone in the stratosphere. CFCs eventually created a hole in the stratosphere, the atmospheric layer that protects the earth from the sun’s UV radiation. Had the hole kept growing, it would have allowed deadly levels of UV radiation to reach earth’s surface, enough to kill off plants and humans alike.

First discovered in the 1970s, the negative impact of CFCs on the ozone was initially met with heavy skepticism and resistance, mainly from the industries that produced, sold and used CFCs.

The CFC problem didn’t become an urgent global issue until the hole in the ozone layer was found over Antarctica in 1985. That discovery led to 46 countries signing the Montreal Protocol, a global treaty ratified in 1987 that established the gradual phasing-out of CFCs.

Today, with the hole over Antarctica gradually getting smaller, the Montreal Protocol is among the most successful and encouraging examples of international environmental, economic and social cooperation.

What chemicals have replaced CFCs?

The quest to replace CFCs has not been without regrettable substitutions, chief among them being the use of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) to replace CFCs. Like CFCs, it turns out HCFCs also deplete the ozone layer, although not to the same extent. HCFCs are also greenhouse gases, which raise the earth’s surface temperature.

HCFCs were eventually replaced by HFCs. However, HFCs are greenhouse gases, too. As such, both HCFCs and HFCs are being phased out under amendments to the Montreal Protocol, and more climate friendly replacements are being proposed. Such replacements include hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) and HFC-HFO blends, as well as “natural” refrigerants such as carbon dioxide, ammonia and propane.

The use of carbon dioxide, ammonia and propane as refrigerants brings us somewhat full circle, since they are either the same or similar to the chemicals replaced by CFCs to begin with.

Coming up in Part III of the Historic Chemical Substitutions series, we’ll go back in time to examine the uses, impacts and replacement of Arsenic Green, one of the first toxic paints but unfortunately not the last.

Chlorofluorocarbon Gases (CFCs) FAQs

“CFC” stands for chlorofluorocarbon gas. CFCs were developed in the 1920s to replace chloromethane and ammonia as refrigerants. Unlike chloromethane and ammonia, CFCs are non-flammable and non-reactive in household settings, posing what was assumed to be less danger to consumers. Common CFCs include freon, R-11 and R-12.

Yes, CFCs solved the safety issues with home refrigerators, preventing property damage and injuries and deaths.

Upon reaching the earth’s atmosphere, CFCs would react with and breakdown ozone molecules. The breakdown of ozone eventually created a hole in the earth’s stratosphere. The stratosphere protects the earth from UV radiation. If the hole had been allowed to get bigger due to CFCs, increasingly dangerous levels of UV radiation would reach our surface, ultimately making life on earth unsustainable.

The Montreal Protocol is global treaty ratified in 1987 in Montreal, QB that established the gradual phasing-out of CFCs and other harmful chemicals in an effort to protect the ozone layer. It is considered among the most successful examples of international cooperation in modern history.

Yes. CFCs are a prime example of successful chemical replacement as they were completely phased out and replaced by HFCs, which were then replaced by HFOs.

CFCs are gradually breaking down over time, so there isn’t a cleanup exactly, but the hole in the ozone layer is getting smaller.

PIn terms of completeness of the ban, there are parallels with the REACH microplastics ban and upcoming REACH PFAS ban. It remains to be seen if any current or future chemical bans will have as much success and/or positive impact as the CFCs ban.