Historic Chemical Substitutions, Part 3: Arsenic Green

It seems like every day there are more headlines about PFAS, a.k.a “Forever Chemicals”, each one identifying more health risks, more places they've been detected, more bans and more regulations.

From the beginning, Actalent has been following PFAS bans and substitution programs closely in our Q&A series, Forever ... For Now. As a society, it’s clear we know and accept that the health risks associated with PFAS greatly outweigh the benefits.

Now comes the process of replacing them.

The prevalence of “forever chemicals” and our reliance on them — they’ve proven extremely useful and effective in everything from long-lasting cosmetics to heat-resistant firefighting foam — will make the transformation anything but simple.

In fact, the process will require major adjustments, both in how we make and use a multitude of affected products.

The good news is we’ve done this before.

In this series, Historic Chemical Substitutions, we’re examining some of the most successful chemical substitution campaigns in history.

Hopefully these examples will serve as reminders that we’ve adjusted, innovated and overcome challenges like PFAS before. And in making these changes, we’ve often achieved better outcomes for the greater good — outcomes that may not have been endeavored otherwise.

In Parts 1 and 2, we examined asbestos and CFCs, respectively. In Part 3, we travel further back in time to the 18th and 19th centuries for a look at the colorful but deadly arsenic green.

Arsenic Green

In the latter 18th century, the vivid emerald colors and durability of arsenic pigments made them incredibly popular and ubiquitous for use in green paints and colorings, replacing copper carbonate pigments like malachite and azurite.

“Scheele’s Green” (copper arsenate), the first type of arsenic green, was named after its inventor Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1775. It was used to color wallpaper, fabrics, books, candles, artificial flowers and even candy. Sheele’s Green was eventually surpassed by another arsenic green, the more vibrant and durable (but still highly toxic) Paris Green.

Among the dangers posed by arsenic green, wallpaper poisoning would occur when arsenic-laden dust particles and poisonous gases would enter the air, especially as surfaces deteriorated or became moldy, causing occupants to become gravely ill. It’s suspected that arsenic green wallpaper may have killed Napoleon

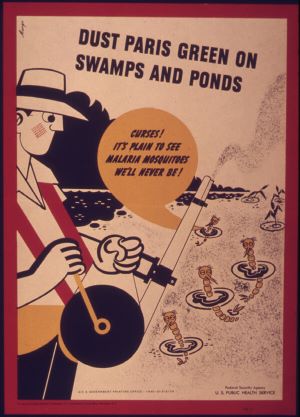

In the latter part of the 19th century, as less toxic paints were being developed, Paris Green became obsolete (but not before it briefly found use in the sewers of Paris and on the farm fields of the U.S., as both a rat poison and insecticide, respectively).

Given its popularity and widespread use in many different aspects of life, arsenic green is a good example that a harmful chemical can be successfully phased out for the good of public health and safety.

Unless, that is, you collect green books from the 19th century.*

But as you’ll read in Part IV of this series, the eventual widespread use of lead paint would pose new poisoning dangers of its own.

*to learn more about the University of Delaware’s Poison Book Project, visit the project website.

Arsenic Green FAQs

Arsenic green refers to a class of pigments made from the poison arsenic that were used as green paints and colorings in the 18th and 19th centuries. The vivid emerald colors and durability of arsenic greens like “Scheele’s Green” and “Paris Green” made them extremely popular.

Yes. Arsenic green would cause “wallpaper poisoning” when arsenic-laden dust particles and poisonous gases would enter the air, especially as surfaces deteriorated or became moldy, causing occupants to become gravely ill. It’s suspected that arsenic green wallpaper may have killed Napoleon.

No. Different pigments could have been used, either greens that are not as vivid or just mix red or blue. The main drawback of not using arsenic green was purely aesthetic, which doesn’t justify the health problems and deaths it caused.

Arsenic green was never officially banned, but it was completely replaced by less toxic paints in the 19th century.

Other than some museum pieces that still pose hazards to curators or perhaps some very old houses with very old wallpapers, it has been completely cleaned up.

Arsenic green has strong parallel to all hazardous chemicals where the danger level isn’t justified by the importance of the use, like PFAS in ski wax or microplastics in face wash, for instance.

PFAS stands for "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances." These chemicals are carbon chains with fluorine atoms. The carbon-fluorine bond is incredibly strong. That means these chemicals persist and accumulate in the environment, some potentially for hundreds of years. In fact, they last longer than any other synthetic chemical that exists. In cases where larger PFAS do break down, they break down into smaller PFAS that then also persist and accumulate.